Listen to This Article:

Long before chefs became household names, Jacques Pépin was in the kitchen: standing over stockpots, turning vegetables by hand, and proving that great cooking begins with sharp skills and steady practice. Born in France and shaped by some of its most demanding kitchens, Pépin arrived in the U.S. in 1959 and has spent decades since sharing his craft with cooks around the world.

Along the way, he cooked alongside legends like Julia Child, turned down a job with the Kennedys, and built a career on a simple belief: lasting skill comes from practicing the basics, again and again. For Pépin, teaching isn’t just part of the job. It’s the heart of it. His lessons still shape kitchens everywhere, from culinary schools to home counters.

From Family Kitchen to Culinary Apprentice: Learning by Doing

At thirteen, Jacques Pépin joined the kitchen as an apprentice, working alongside his mother in their family’s restaurant, Le Grand Hôtel de Mûrat, in Bourg-en-Bresse, France. There were no formal lessons or written recipes, just long hours of peeling vegetables, cleaning fish, and learning each station.

“I was learning a discipline that would last a lifetime,” he wrote in his memoir The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen.

The choice to become a cook felt obvious to Pépin. It was either join his mother in the kitchen or follow in his dad’s footsteps as a cabinet maker.

“Cooking for me was more exciting, and so I went into that world and never regretted it,” he said.

At the time, cooking in France wasn’t seen as a prestigious profession.

“Parents aspired for their child to be a lawyer or a doctor, but not a cook,” he recalled. “So we were very low on the social scale.”

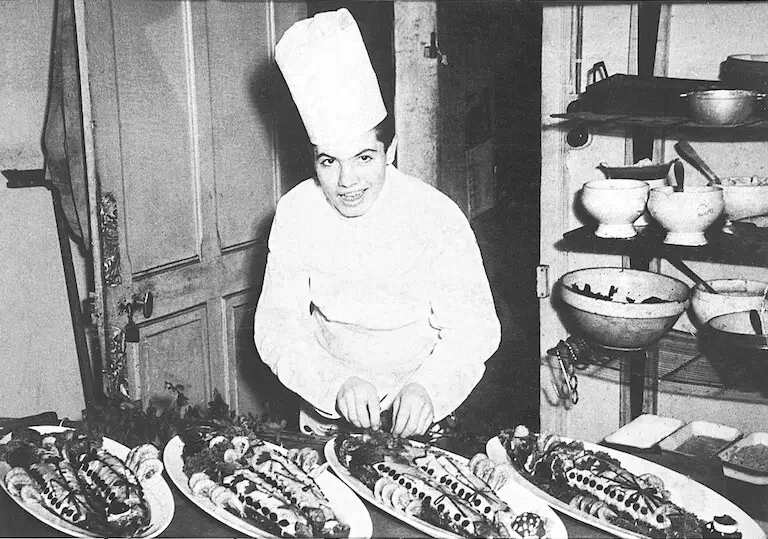

Pépin’s path took him from his family’s kitchen to some of France’s most respected restaurants, including the Grand Hôtel de l’Europe, Plaza Athénée, and Fouquet’s in Paris. Within the strict brigade system, he refined his technique with focus and consistency. By his early twenties, he was cooking for French President Charles de Gaulle and his family. Madame de Gaulle affectionately referred to Pépin as “petit Jacques” as they had a close, personal connection with one another that extended beyond their professional roles. Pépin was responsible for planning weekly menus and preparing the family’s Sunday meal (often poulet chasseur, a family favorite) for enjoyment after church, as they were devout Catholics.

In 1959, Pépin looked beyond the rigid hierarchy of French kitchens and crossed the Atlantic in search of new opportunity. What he found in the U.S. would transform not only his own career, but also how the world thought about chefs and culinary education.

Jacques Pépin was working in some of the most prestigious kitchens in France by his early twenties.

The American Chapter: From Le Pavillon to Julia Child

When Pépin arrived in New York City, he joined the kitchen at Le Pavillon, the city’s most renowned French restaurant. Not long after, he was offered a position cooking for President John F. Kennedy. Pépin famously turned it down.

“Cooking for the Kennedys would have been very glamorous,” he wrote in his memoir, “but I wanted to work in restaurants and learn about the business of food.”

Reflecting on the decision, Pépin has noted the cultural differences between the U.S. and France’s approach to food at the time. In France, chefs held low social status, whereas in America, the profession was beginning to garner more respect. New to the country, he said he didn’t fully grasp the prestige or honor of being asked to cook for the president.

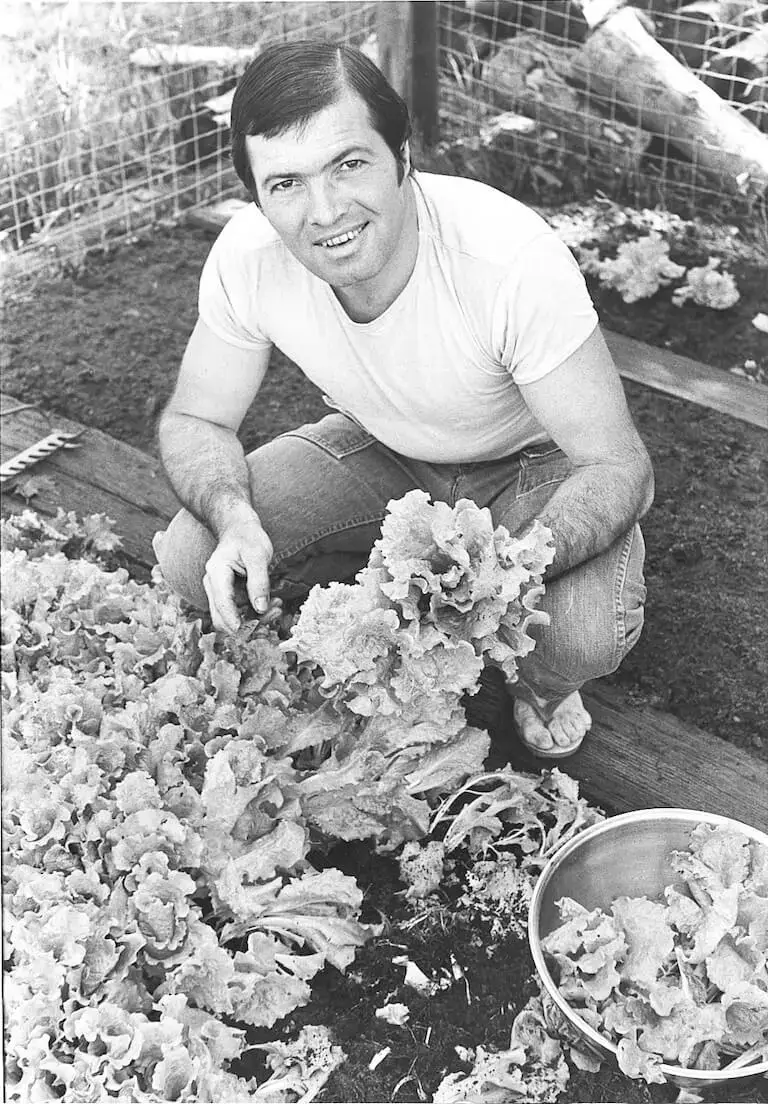

Instead, he joined Howard Johnson’s, helping develop recipes and systems for the nationwide chain. Pépin took the role because of the company’s commitment to sourcing quality ingredients, a non-negotiable in his eyes. As he later said, “This is where it all starts. If you want to cut corners and buy lower quality ingredients, you are not going to have great results, there is just no way.”

Jacques Pépin has always focused on fresh, quality ingredients.

During those early years in the U.S., Pépin also met Julia Child and James Beard. In the 1960s and 1970s, American home cooking often leaned on convenience foods: canned goods, boxed mixes, and casseroles built on processed ingredients. Pépin, Child, and Beard shared a different vision, one rooted in classic French techniques, fresh ingredients, and the belief that cooking from scratch was both achievable and worth the effort.

Together, through cooking shows—including the PBS series Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home—in-person appearances, and various cookbooks, they helped introduce a generation of American cooks to the fundamentals of good technique, showing that skills like sauce-making, knife work, and seasoning weren’t just for restaurants.

A Life-Altering Accident and the Call to Teach

A near-fatal car accident in 1974 forced Pépin to step away from the demands of restaurant kitchens. The crash left him with multiple injuries, including two broken arms. His left arm was so severely damaged that doctors initially considered amputation. Although he recovered, the physical toll made it impossible to continue the grueling pace of professional kitchen work.

Instead of slowing down, Pépin shifted his focus to teaching, writing, and television—a move that would define the next chapter of his career.

By 1982, he had joined the newly formed French Culinary Institute in New York City as a Dean, helping shape its curriculum and mentoring a generation of young chefs. In 1989, Pépin and Child teamed up to create a culinary certificate program at Boston University’s Metropolitan College, one of the first university-level culinary programs in the country.

The Pépin Philosophy: What Every Cook Should Know

Pépin returned time and again to a few core ideas that remain at the heart of culinary education: develop the fundamental techniques, respect the ingredients, and never stop learning.

Technique as a Gateway to Freedom

For Pépin, good cooking starts with understanding and implementing the fundamentals. He believes that true confidence comes from perfecting small, essential tasks, like slicing an onion evenly, skimming a simmering stock, or emulsifying a perfect vinaigrette. For Pépin, technique was never about rigid perfection. He saw it as a foundation that gave cooks the freedom to adapt, improvise, and create with confidence.

“As chefs, the trick is to know the basic technique and then to repeat and repeat and repeat it,” Pépin said in an interview with Luxeat. “That’s how I’m able to cook on television, looking at the camera and talking while I’m doing it, because my hands work by themselves. It becomes part of your DNA.”

Simplicity and Ingredient Respect

Although he could prepare elaborate dishes like lobster soufflé or Chateaubriand, Pépin believed that even the simplest dish deserved just as much care. He often reminded cooks that technique wasn’t about complexity, it was about understanding how ingredients behave and treating them accordingly.

“When you watch Jacques cook, he does all of these things where he’s actually executing perfect technique, but he just makes it look so simple and easy,” said Dr. Rollie Wesen, executive director of the Jacques Pépin Foundation. One example he gave was butter-glazed asparagus.

“He cut the asparagus into small pieces raw, threw it into a saute pan, put three or four tablespoons of water in there, cranked up the heat, and put the lid on it just for two or three minutes… Took off the lid, there was still just a little bit of water left in the pan, threw in a couple of tablespoons of butter. Toss, toss, toss, and then that butter in that tossing is actually emulsifying into the water. You’re making, basically, a quick beurre blanc… You have perfectly cooked and butter-glazed asparagus.”

Contrast this with the more traditional, multi-step approach—blanching, setting aside, making a beurre blanc separately, then plating, and Dr. Wesen says, “because he knows how to do all those things and knows how things work, has this language of cooking, language of technique, he can just do it in a few seconds and make it look quite easy.”

The classic French omelet is another favorite teaching tool. Whether on his Essential Pépin series, a YouTube clip, or in countless PBS demonstrations, Pépin uses it to show that a perfectly cooked omelet—tender, rolled, and without browning—demands as much finesse as any intricate dish.

Jacques Pépin demonstrates how to make an omelet

This philosophy also came to life in Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home, where Pépin and longtime friend Julia Child brought simple and classic recipes like roast chicken, omelets, and beef stews into American homes. The show celebrated unfussy food and focused on foundational skills, but it was their dynamic that truly made it shine. They bickered gently over seasoning (“needs more salt!”), debated the best way to truss a chicken, and playfully stole each other’s mise en place.

The opening moments of each episode often set the tone, lighthearted and almost always theatrical. In one, Julia summoned Jacques using a wooden duck call before diving into a lineup of duck recipes; in another, they exchanged limericks like old friends with a shared sense of mischief.

Whether they were bantering or bickering or giving a soup an extra stir, their show of techniques shine through. As Pépin wrote in his cookbook, “While food trends change, basic techniques do not.”

Jacques Pépin and Julia Child teamed up often throughout the years.

Cooking as a Lifelong Practice

Pépin often described himself as a lifelong student of cooking. He approaches each dish with curiosity and a willingness to learn something new.

In an interview with Bon Appétit, he reflected on this very idea, saying, “I work with some youngsters, and I’ll say, ‘Wow, I never thought of doing something this way.’” Even after decades in the kitchen, he still finds inspiration in watching others cook.

Dr. Rollie Wesen recalled one such moment while the two were filleting salmon for a party. Wesen began using a technique he’d recently learned of removing the fillet with just the back of his hand, no knife required.

“He’s like, ‘What are you doing? You’re not even using a knife; you’re just using your hand.’ He jumped right in—87 years old—and he’s learning how to fillet a salmon in a new way,” Wesen said.

Whether teaching culinary students or home cooks, Pépin encourages humility and the idea that cooking is a craft you refine over time. For anyone considering entering the culinary field, this lesson remains one of his most enduring. No matter how much you know, there is always more to discover, and each day in the kitchen is an opportunity to grow.

Beyond the Kitchen: Mentor, Teacher, Legacy Builder

In 2016, Pépin and his family launched the Jacques Pépin Foundation (JPF) to help expand access to culinary training for people facing employment barriers, such as those in reentry programs, recovery, or transitional housing.

Through grants, scholarships, and curriculum support, the Foundation partners with community kitchens and culinary nonprofits around the U.S., offering practical, life-changing skills rooted in classic technique. It also hosts the Jacques Pépin Video Recipe Book, a free online library featuring hundreds of instructional videos—everything from fridge soup to chicken persillade to a tomato sandwich made from leftover bread.

These days, you can also catch him teaching someone to break down a chicken on Youtube videos or casually prepping summer appetizers for friends over a game of boules.

The Jacques Pépin Foundation partners with community kitchens and culinary nonprofits around the U.S, including NECAT, New England Culinary Arts Training, a non-profit organization using culinary arts training to transform lives by providing a tuition-free program focused on wellness and career readiness.

Join the Celebration: 90 Years, 90 Chefs, One Culinary Legend

Chef Jacques Pépin turns 90 in December. To mark this milestone, the Jacques Pépin Foundation has launched the 90/90 Campaign—celebrating his extraordinary career and spreading awareness of the Foundation’s mission to expand free culinary training for individuals facing employment barriers.

For culinary students and aspiring chefs, this is an opportunity to honor the techniques and values that have shaped modern culinary education. Whether you’re honing your knife skills, practicing mother sauces, or learning the art of a French omelet, you’re building on foundations that Chef Pépin helped establish.

Get involved in multiple ways:

- Attend a celebration dinner: Top chefs and restaurants across the country are hosting 90 celebration dinners, with proceeds supporting the Jacques Pépin Foundation and its mission to empower communities through culinary education.

- Join virtual events: Participate in online cooking demonstrations and special events that honor Chef Pépin’s legacy and raise support for culinary education.

- Host your own gathering: Access the Home Cook Toolkit at celebratejacques.org, featuring menu inspiration from Jacques’ most beloved dishes, customizable templates, and fundraising tools.

The Pépin Lesson: Stay Curious, Stay Craft-Driven

Across more than seventy years, Jacques Pépin continues to show that great cooking rests on a few enduring values: solid technique, respect for ingredients, and a commitment to learning. Whether in professional kitchens, on television, or in kitchen classrooms, he proved that lasting success comes from dedication to craft and a willingness to share what you know.

His message remains clear. Learn the fundamentals. Practice them every day. Stay curious. And when the time comes, pass those lessons on.